European cuisine

European cuisine comprises the cuisines of Europe[1][2] including the cuisines brought to other countries by European settlers and colonists. Sometimes the term "European", or more specifically "continental" cuisine, is used to refer more strictly to the cuisine of the western parts of mainland Europe.

.jpg.webp)

The cuisines of Western countries are diverse, although there are common characteristics that distinguish them from those of other regions.[3] Compared with traditional cooking of East Asia, meat is more prominent and substantial in serving size.[4] Steak and cutlets in particular are common dishes across the West. Western cuisines also emphasize grape wine and sauces as condiments, seasonings, or accompaniments (in part due to the difficulty of seasonings penetrating the often larger pieces of meat used in Western cooking). Many dairy products are utilised in cooking.[5] There are hundreds of varieties of cheese and other fermented milk products. White wheat-flour bread has long been the prestige starch, but historically, most people ate bread, flatcakes, or porridge made from rye, spelt, barley, and oats.[6][7] The better-off also made pasta, dumplings and pastries. The potato has become a major starch plant in the diet of Europeans and their diaspora since the European colonisation of the Americas. Maize is much less common in most European diets than it is in the Americas; however, corn meal (polenta or mămăligă) is a major part of the cuisine of Italy and the Balkans. Although flatbreads (especially with toppings such as pizza or tarte flambée) and rice are eaten in Europe, they are only staple foods in limited areas, particularly in Southern Europe. Salads (cold dishes with uncooked or cooked vegetables, sometimes with a dressing) are an integral part of European cuisine.

Formal European dinners are served in distinct courses. European presentation evolved from service à la française, or bringing multiple dishes to the table at once, into service à la russe, where dishes are presented sequentially. Usually, cold, hot and savoury, and sweet dishes are served strictly separately in this order, as hors d'oeuvre (appetizer) or soup, as entrée and main course, and as dessert. Dishes that are both sweet and savoury were common earlier in Ancient Roman cuisine, but are today uncommon, with sweet dishes being served only as dessert. A service where the guests are free to take food by themselves is termed a buffet, and is usually restricted to parties or holidays. Nevertheless, guests are expected to follow the same pattern.

Historically, European cuisine has been developed in the European royal and noble courts. European nobility was usually arms-bearing and lived in separate manors in the countryside. The knife was the primary eating implement (cutlery), and eating steaks and other foods that require cutting followed. This contrasted with East Asian cuisine, where the ruling class were the court officials, who had their food prepared ready to eat in the kitchen, to be eaten with chopsticks. The knife was supplanted by the spoon for soups, while the fork was introduced later in the early modern period, ca. 16th century. Today, most dishes are intended to be eaten with cutlery and only a few finger foods can be eaten with the hands in polite company.

History

Medieval

In medieval times, a person's diet varied depending on their social class. Cereal grains made up a lot of a medieval person's diet, regardless of social class. Bread was common to both classes- it was taken as a lunch for the working man, and thick slices of it were used as plates called trenchers.[8] People of the noble class had access to finely ground flours for their breads and other baked goods. Noblemen were allowed to hunt for deer, boar, rabbits, birds, and other animals, giving them access to fresh meat and fish for their meals.[9] Dishes for people of these classes were often heavily spiced.[10] Spices at that time were very expensive, and the more spices used in dishes, the more wealth the person had to be able to purchase such ingredients. Common spices used were cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg, pepper, cumin, cloves, turmeric, anise, and saffron.[11] Other ingredients used in dishes for the nobility and clergy included sugar, almonds and dried fruits like raisins.[12] These imported ingredients would have been very expensive and nearly impossible for commoners to obtain. When banquets were held, the dishes served would be very spectacular- another way for the noblemen to show how rich they were. Sugar sculptures would be placed on the tables as decoration and to eat, and foods would be dyed vibrant colors with imported spices.[13]

The diet of a commoner would have been much more simple. Strict poaching laws prevented them from hunting, and if they did hunt and were caught, they could have parts of their limbs cut off or they could be killed.[14] Much of the commoners food would have been preserved in some way, such as through pickling or by being salted.[15] Breads would have been made using rye or barley, and any vegetables would likely have been grown by the commoners themselves.[16] Peasants would have likely been able to keep cows, and so would have access to milk, which then allowed them to make butter or cheese.[17] When meat was eaten, it would have been beef, pork, or lamb. Commoners also ate a dish called pottage, a thick stew of vegetables, grains, and meat.[18]

Early modern era

In the early modern era, European cuisine saw an influx of new ingredients due to the Columbian Exchange, such as the potato, tomato, eggplant, chocolate, bell pepper, pumpkins, and other squash. Distilled spirits, along with tea, coffee, and chocolate were all popularized during this time. In the 1780s, the idea of the modern restaurant was introduced in Paris; the French Revolution accelerated its development, quickly spreading around Europe.

Central European cuisines

All of these countries have their specialities.[19] Austria is famous for Wiener Schnitzel - a breaded veal cutlet served with a slice of lemon, the Czech Republic for world renowned beers. Germany for world-famous wursts, Hungary for goulash. Slovakia is famous for gnocchi-like Halusky pasta. Slovenia is known for German and Italian influenced cuisine, Poland for world-famous Pierogis which are a cross between a ravioli and an empanada. Liechtenstein and German speaking Switzerland are famous for Rösti and French speaking Switzerland for fondue and Raclettes.

- Ashkenazi Jewish cuisine

Austrian cuisine

Austrian cuisine

Czech cuisine

Czech cuisine

German cuisine

German cuisine

Hungarian cuisine

Hungarian cuisine Polish cuisine

Polish cuisine

Liechtensteiner cuisine

Liechtensteiner cuisine Silesian cuisine

Silesian cuisine Slovak cuisine

Slovak cuisine Slovenian cuisine

Slovenian cuisine Swiss cuisine

Swiss cuisine

Austrian strudel

Austrian strudel Austrian Wiener Schnitzel

Austrian Wiener Schnitzel Czech Smažený sýr

Czech Smažený sýr Czech Svíčková

Czech Svíčková German Currywurst

German Currywurst German potato salad

German potato salad German Sauerbraten

German Sauerbraten Hungarian goulash

Hungarian goulash Polish bagel

Polish bagel Polish pierogi

Polish pierogi Slovakian Bryndzové halušky

Slovakian Bryndzové halušky Slovenian Idrijski žlikrofi

Slovenian Idrijski žlikrofi Slovenian Prekmurska gibanica

Slovenian Prekmurska gibanica Swiss fondue

Swiss fondue Swiss raclette

Swiss raclette

Eastern European cuisines

Armenian cuisine

Armenian cuisine Azerbaijani cuisine

Azerbaijani cuisine Belarusian cuisine

Belarusian cuisine Bulgarian cuisine

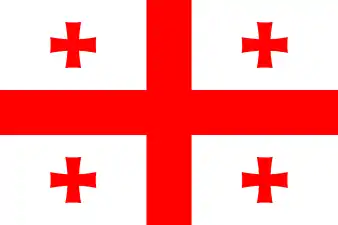

Bulgarian cuisine Georgian cuisine

Georgian cuisine Kazakh cuisine

Kazakh cuisine Moldovan cuisine

Moldovan cuisine

Ossetian cuisine

Ossetian cuisine Romanian cuisine

Romanian cuisine Russian cuisine

Russian cuisine

Ukrainian cuisine

Ukrainian cuisine

Armenian khorovats

Armenian khorovats Azerbaijani Gürzə

Azerbaijani Gürzə Bashkir and Tatar Öçpoçmaq

Bashkir and Tatar Öçpoçmaq Belarusian potato babka

Belarusian potato babka Bulgarian banitsa

Bulgarian banitsa Circassian Haliva

Circassian Haliva Crimean Tatar chiburekki

Crimean Tatar chiburekki Georgian khachapuri

Georgian khachapuri.jpg.webp) Kazakh beshbarmak

Kazakh beshbarmak Moldovan Tochitură

Moldovan Tochitură Romanian Cocoloși

Romanian Cocoloși Romanian mititei

Romanian mititei Russian beef Stroganoff

Russian beef Stroganoff Russian pirozhki

Russian pirozhki Russian pelmeni

Russian pelmeni Ukrainian borscht

Ukrainian borscht Ukrainian pampushka

Ukrainian pampushka Ukrainian pysanka

Ukrainian pysanka

Northern European cuisines

Danish cuisine

Danish cuisine

Estonian cuisine

Estonian cuisine Finnish cuisine

Finnish cuisine Icelandic cuisine

Icelandic cuisine Latvian cuisine

Latvian cuisine Lithuanian cuisine

Lithuanian cuisine Livonian cuisine

Livonian cuisine Norwegian cuisine

Norwegian cuisine Sami cuisine

Sami cuisine Swedish cuisine

Swedish cuisine

Danish stegt flæsk

Danish stegt flæsk Estonian kama dessert

Estonian kama dessert Faroese tvøst og spik

Faroese tvøst og spik Finnish leipäjuusto

Finnish leipäjuusto Icelandic Hákarl

Icelandic Hákarl

Latvian layered rye bread

Latvian layered rye bread Lithuanian cepelinai

Lithuanian cepelinai Norwegian fårikål

Norwegian fårikål Norwegian lefse

Norwegian lefse Sami Sautéed reindeer

Sami Sautéed reindeer Swedish cinnamon roll

Swedish cinnamon roll.jpg.webp) Swedish smörgåsbord

Swedish smörgåsbord Swedish surströmming

Swedish surströmming

Southern European cuisines

Albanian cuisine

Albanian cuisine Aromanian cuisine

Aromanian cuisine Bosnian cuisine

Bosnian cuisine Croatian cuisine

Croatian cuisine Cypriot cuisine

Cypriot cuisine Gibraltarian cuisine

Gibraltarian cuisine Greek cuisine

Greek cuisine

Italian cuisine

Italian cuisine

Macedonian cuisine

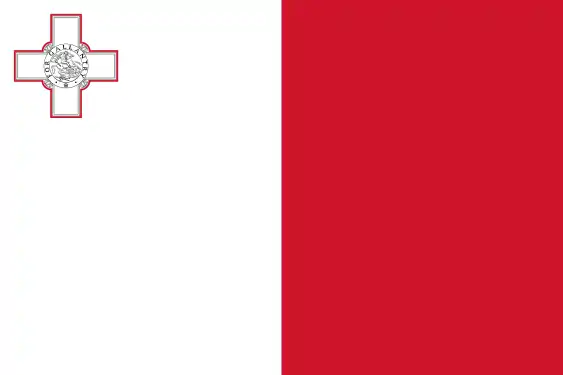

Macedonian cuisine Maltese cuisine

Maltese cuisine Montenegrin cuisine

Montenegrin cuisine.svg.png.webp) Ottoman cuisine

Ottoman cuisine Portuguese cuisine

Portuguese cuisine Sammarinese cuisine

Sammarinese cuisine- Sephardic Jewish cuisine

Serbian cuisine

Serbian cuisine

Spanish cuisine

Spanish cuisine

Turkish cuisine

Turkish cuisine

Albanian Tavë kosi

Albanian Tavë kosi.jpg.webp) Andalusian gazpacho

Andalusian gazpacho Aromanian Metsovone

Aromanian Metsovone Balearic ensaïmada

Balearic ensaïmada Basque talo

Basque talo Bosnian ćevapi

Bosnian ćevapi Canarian Papas arrugadas

Canarian Papas arrugadas Catalan pa amb tomàquet

Catalan pa amb tomàquet Cretan Dakos

Cretan Dakos Croatian Licitar

Croatian Licitar Croatian Zagorski štrukli

Croatian Zagorski štrukli Cypriot Afelia

Cypriot Afelia Gibraltarian japonesa

Gibraltarian japonesa Greek gyros

Greek gyros Greek spanakopita

Greek spanakopita Greek souvlaki

Greek souvlaki Italian gelato

Italian gelato Italian polenta

Italian polenta Italian ravioli

Italian ravioli Lombard risotto

Lombard risotto_(3).jpg.webp) Macedonian Tavče gravče

Macedonian Tavče gravče Madrilenian squid sandwich

Madrilenian squid sandwich Maltese pastizz

Maltese pastizz.jpg.webp) Montenegrin njeguški pršut

Montenegrin njeguški pršut Neapolitan pizza

Neapolitan pizza Portuguese bacalhau

Portuguese bacalhau Portuguese Cozido à portuguesa

Portuguese Cozido à portuguesa Roman carbonara

Roman carbonara Sammarinese Bustrengo

Sammarinese Bustrengo Sardinian casu martzu

Sardinian casu martzu Serbian Pljeskavica

Serbian Pljeskavica.jpg.webp) Sicilian cannoli

Sicilian cannoli Spanish empanada

Spanish empanada

Spanish tapas

Spanish tapas.jpg.webp) Turkish doner kebab

Turkish doner kebab Turkish macun

Turkish macun Valencian paella

Valencian paella Venetian carpaccio

Venetian carpaccio

Western European cuisines

.svg.png.webp) Belgian cuisine

Belgian cuisine British cuisine

British cuisine

Dutch cuisine

Dutch cuisine French cuisine

French cuisine

Irish cuisine

Irish cuisine Luxembourgian cuisine

Luxembourgian cuisine- Mennonite cuisine

Monégasque cuisine

Monégasque cuisine Occitan cuisine

Occitan cuisine

Belgian moules-frites

Belgian moules-frites Belgian waffle

Belgian waffle British bangers and mash

British bangers and mash British full breakfast

British full breakfast British Sunday roast

British Sunday roast Cornish pasty

Cornish pasty Corsican fritelli

Corsican fritelli Dutch kibbeling

Dutch kibbeling

English Christmas pudding

English Christmas pudding English fish and chips

English fish and chips.JPG.webp) English roast beef

English roast beef French escargot

French escargot_-_pot_au_feu_arm%C3%A9nien.jpg.webp) French pot-au-feu

French pot-au-feu French quiche

French quiche

Irish breakfast roll

Irish breakfast roll

Jersey wonders

Jersey wonders Luxembourgian Judd mat Gaardebounen

Luxembourgian Judd mat Gaardebounen

Monégasque Barbajuan

Monégasque Barbajuan Northern Irish pastie supper

Northern Irish pastie supper Occitan aligot

Occitan aligot Scottish haggis

Scottish haggis Scottish Scotch pie

Scottish Scotch pie Welsh crumpet

Welsh crumpet

See also

References

- Culinary Cultures of Europe: Identity, Diversity and Dialogue. Council of Europe.

- "European Cuisine." Europeword.com Archived 2017-10-09 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed July 2011.

- Kwan Shuk-yan (1988). Selected Occidental Cookeries and Delicacies, p. 23. Hong Kong: Food Paradise Pub. Co.

- Lin Ch'ing (1977). First Steps to European Cooking, p. 5. Hong Kong: Wan Li Pub. Co.

- Kwan Shuk-yan, pg 26

- Alfio Cortonesi, "Self-sufficiency and the Market: Rural and Urban Diet in the Middle Ages", in Jean-Louis Flandrin, Massimo Montanari, Food: A Culinary History from Antiquity to the Present, 1999, ISBN 0231111541, p. 268ff

- Michel Morineau, "Growing without Knowing Why: Production, Demographics, and Diet", in Jean-Louis Flandrin, Massimo Montanari, Food: A Culinary History from Antiquity to the Present, 1999, ISBN 0231111541, p. 380ff

- "British Library". www.bl.uk. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- "Middle Ages Food and Diet". www.lordsandladies.org. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- "British Library". www.bl.uk. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- "Middle Ages Food and Diet". www.lordsandladies.org. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- "British Library". www.bl.uk. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- "British Library". www.bl.uk. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- "Middle Ages Food and Diet". www.lordsandladies.org. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- "British Library". www.bl.uk. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- "Middle Ages Food and Diet". www.lordsandladies.org. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- "Middle Ages Food and Diet". www.lordsandladies.org. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- "British Library". www.bl.uk. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- "Cuisine from Central Europe". Visit Europe. Archived from the original on 23 August 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

Further reading

- Albala, Ken (2003). Food in Early Modern Europe. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313319626. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- R & R Publishing (2005). European Cuisine: The Best in European Food. Cpg Incorporated. ISBN 1740225279. Retrieved 6 June 2017.